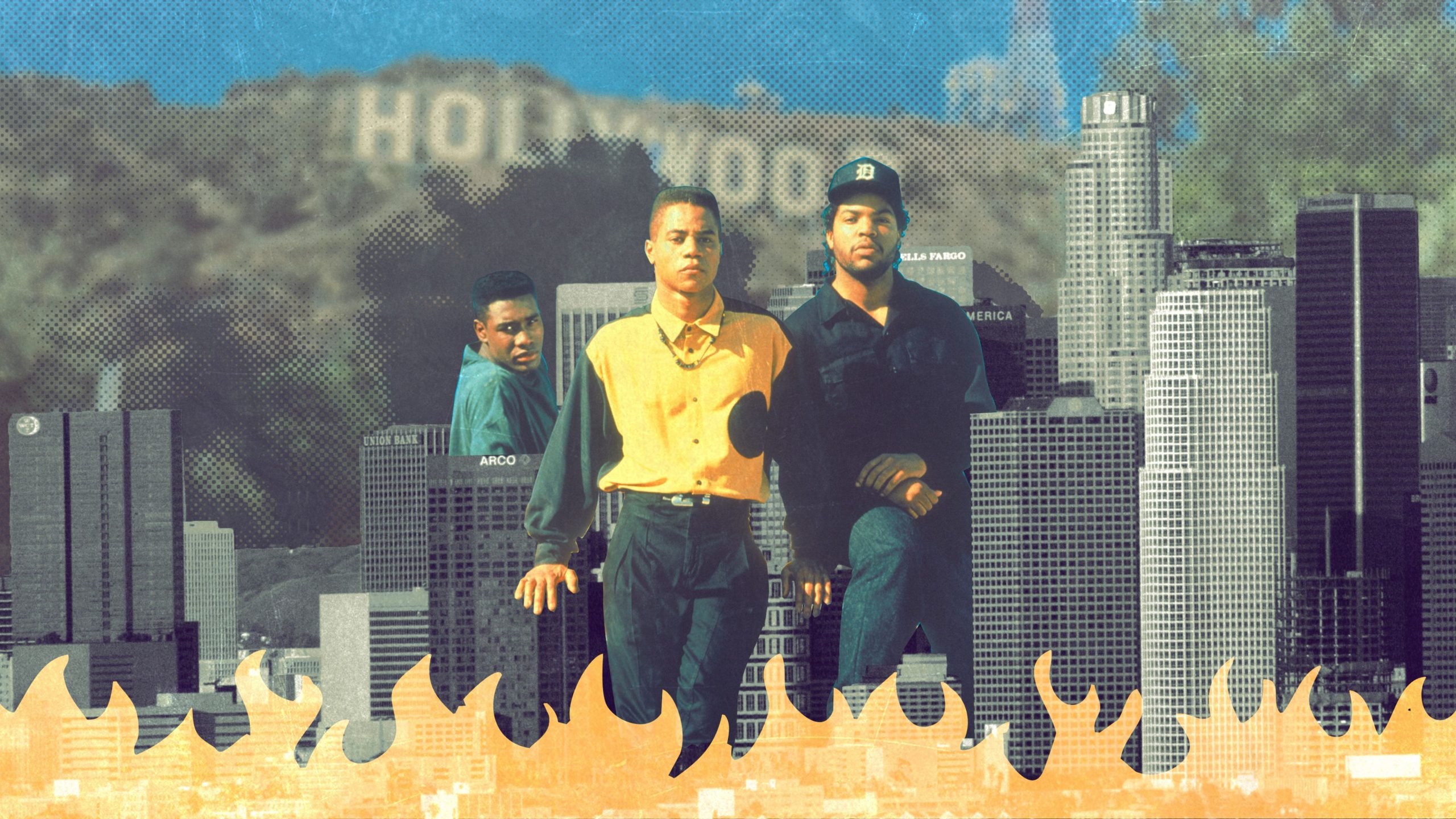

most famous line from John Singleton’s 1991 debut, Boyz n the Hood, strikes a chord because it’s so reflective of the era in which the film was released. In the final scene, a solemn Doughboy (played by rookie actor Ice Cube) offers a sobering perspective on how the world feels about places like South Los Angeles: “Either they don’t know, don’t show, or don’t care about what’s going on in the hood.” Telling Black stories from a place of authenticity was Singleton’s mission, beginning with Boyz n the Hood, which he wrote and directed almost immediately after he graduated from the University of Southern California in 1990. Boyz n the Hood, the tale of three young men trying to survive South L.A., melded gutting realism with coming-of-age earnestness. It was instantly hailed as a cinematic achievement, praised for being brilliant, pioneering, and essential. But for a brief period of time, there were concerns over whether or not it was dangerous.

After impressing audiences at the 1991 Cannes Film Festival and drawing critical acclaim ahead of its release, Boyz n the Hood opened in 829 theaters on July 12, 1991, raking in over $10 million during its first weekend. Unfortunately, violence broke out in theaters showing Boyz n the Hood across the nation and threatened to overshadow its otherwise successful opening. Two people were killed and more than 30 were injured in incidents that took place in 12 states. Some theaters canceled screenings; others took additional precautions, including installing metal detectors and employing extra security. Columbia Pictures elected not to remove the film from distribution, instead offering to pay for extra security should any theater request it. In a truly insulting moment, Singleton was forced to defend Boyz n the Hood against allegations that the film should be held accountable. “I didn’t create the conditions under which people shoot each other,” Singleton said during an ensuing press conference. “This happens because there’s a whole generation of people who are disenfranchised.” (Singleton reportedly called the focus on the violence “artistic racism.”) And what makes the claim so ridiculous is that Boyz n the Hood, with its “Increase the peace” tagline, is decidedly anti-violent.

Boyz n the Hood follows the bright Tre (Cuba Gooding Jr.), his friend and prodigious athlete Ricky (Morris Chestnut), and Ricky’s half-brother, Doughboy—a knucklehead who’s done bad things, but isn’t bad at his core. As they navigate their surroundings, the film delivers overt messages about the indispensability of positive role models, the threat of gentrification, and valuing life despite growing up in an environment where the slightest disrespect can sign your death certificate. By going wide and examining the societal factors that created these circumstances, Boyz n the Hood highlights why incidents like stabbings, shootings, and fights at movie theaters occur. “I think, from a sociological standpoint, he really illustrated what kinds of conditions lead to those kinds of actions,” Stephanie Allain, a producer who was an executive at Columbia Pictures at the time, says of Singleton. But because the film depicted gang culture (if only to dissuade), it was accused of glorifying violence and attracting gangs.

“The movie was about gangs,” Roger Hom, then a deputy with the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department, told the Associated Press about the theater violence in 1991. “With the incidents occurring elsewhere, you can draw your own conclusions.” No one has to think too hard to draw their own conclusions about what a statement like that means: that certain films—Black films, specifically—cause violence because they depict it. Roger Ebert, who gave Boyz n the Hood four stars, defended the film with the reminder that gangs are not its central focus: “It would be tragic if this statement about gang violence was suppressed in any way.” But this was a different time: an era before hip-hop was recognized as the popular music, rappers like Ice Cube were mainstream figures, and Black cinema as we now know it had caught on with the masses.

By 1991, Singleton, along with the likes of Spike Lee and Reginald and Warrington Hudlin, was at the forefront of an emerging class of Black filmmakers. The week Boyz n the Hood opened, Singleton’s newfound success was the lead of a New York Times Magazine story about the rise of Black filmmakers titled “They’ve Gotta Have Us.” Despite Hollywood’s interest in Black stories, the desire to be entertained by Black people (or to profit from that entertainment) doesn’t equate to appreciating or respecting them. And despite the commendation Boyz n the Hood received, the concern over its supposed “dangerous” qualities reflects a culture of fear steeped in racism.

moment that should’ve been a victory lap for Allain and Columbia Pictures soured quickly. Allain was on a retreat in Santa Barbara, California, along with fellow Columbia executives including Frank Price, Peter Guber, Jon Peters, and Amy Pascal when Boyz n the Hood hit theaters. Spirits were high, especially since it was Allain who got hold of Singleton’s script after meeting him roughly a year prior. “We were all at some fancy hotel, we’d had some retreats that day, we were getting the numbers, they were really good, and everybody was happy,” Allain says. “In fact, we did a little caravan where we drove out to some movie theaters in areas of Santa Barbara. They were packed. And we’re like, ‘Oh my God, it worked, it worked, it worked!’” But the mood changed dramatically by the day’s end.

“That night, just as I was kind of dozing off to sleep, Amy called me from her room and said, ‘People are hurt, people are dying,’” Allain remembers. “And … I literally went into shock. I was just so upset. And because the entire time, and even during the whole campaign, we just kept reiterating that the reason the movie was made was to increase the peace. The reason the movie was made was because we wanted to make a statement about kids in these situations and, through Tre’s journey, making the right choice.”

“I think if there’s a shooting at a white movie, people are going to just dismiss it as a coincidence. They’re not going to read anything into it beyond a shooting at a movie.” —Dr. Todd Boyd, professor of cinema and media studies at USC

Allain was reassured this wasn’t her fault (“I was told, ‘You did everything you could,’” she recalls), but the scenario forced Columbia to consider not showing Boyz n the Hood in certain theaters. “There was a lot of talk about holding theaters that were in urban areas,” Allain says. “Because there was fear out there already.” Columbia stood behind Boyz n the Hood, leaving the decision to pull it in the hands of individual theaters. Capitulating to the negative press, even as a preventative measure, would’ve validated the notion that a film that featured violence only to underscore why it occurred was actually responsible for it.

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.